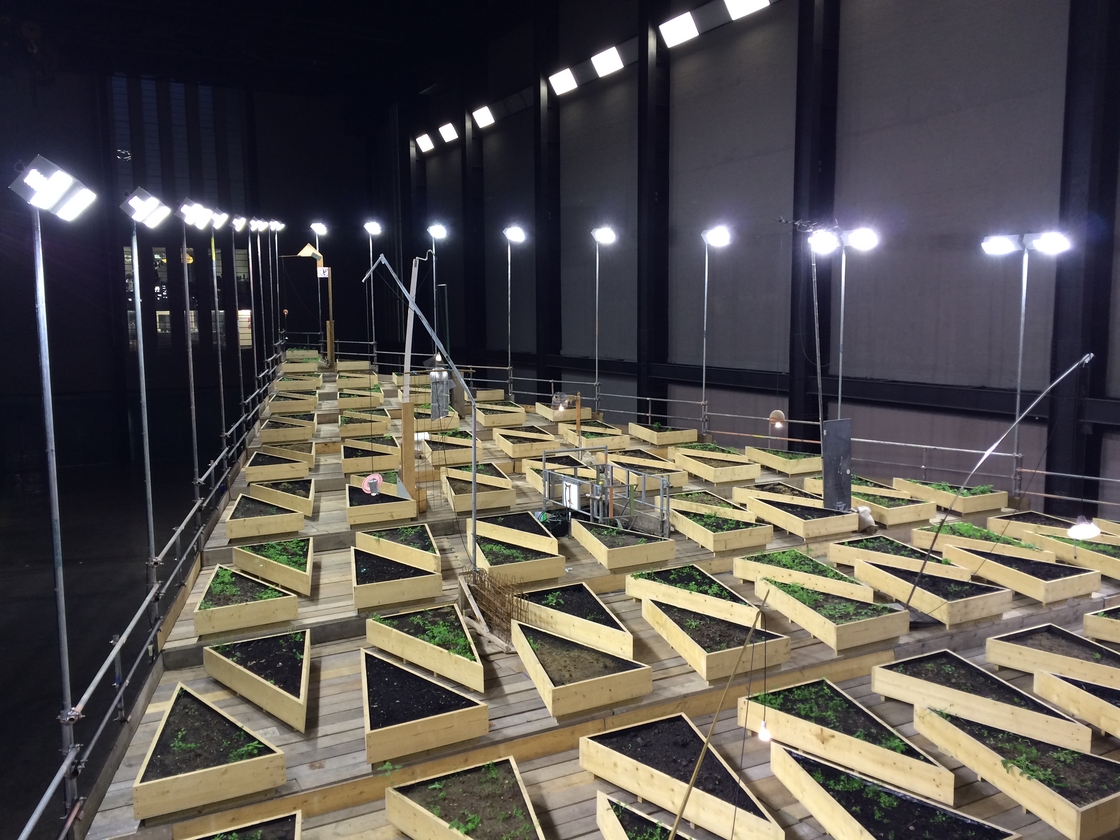

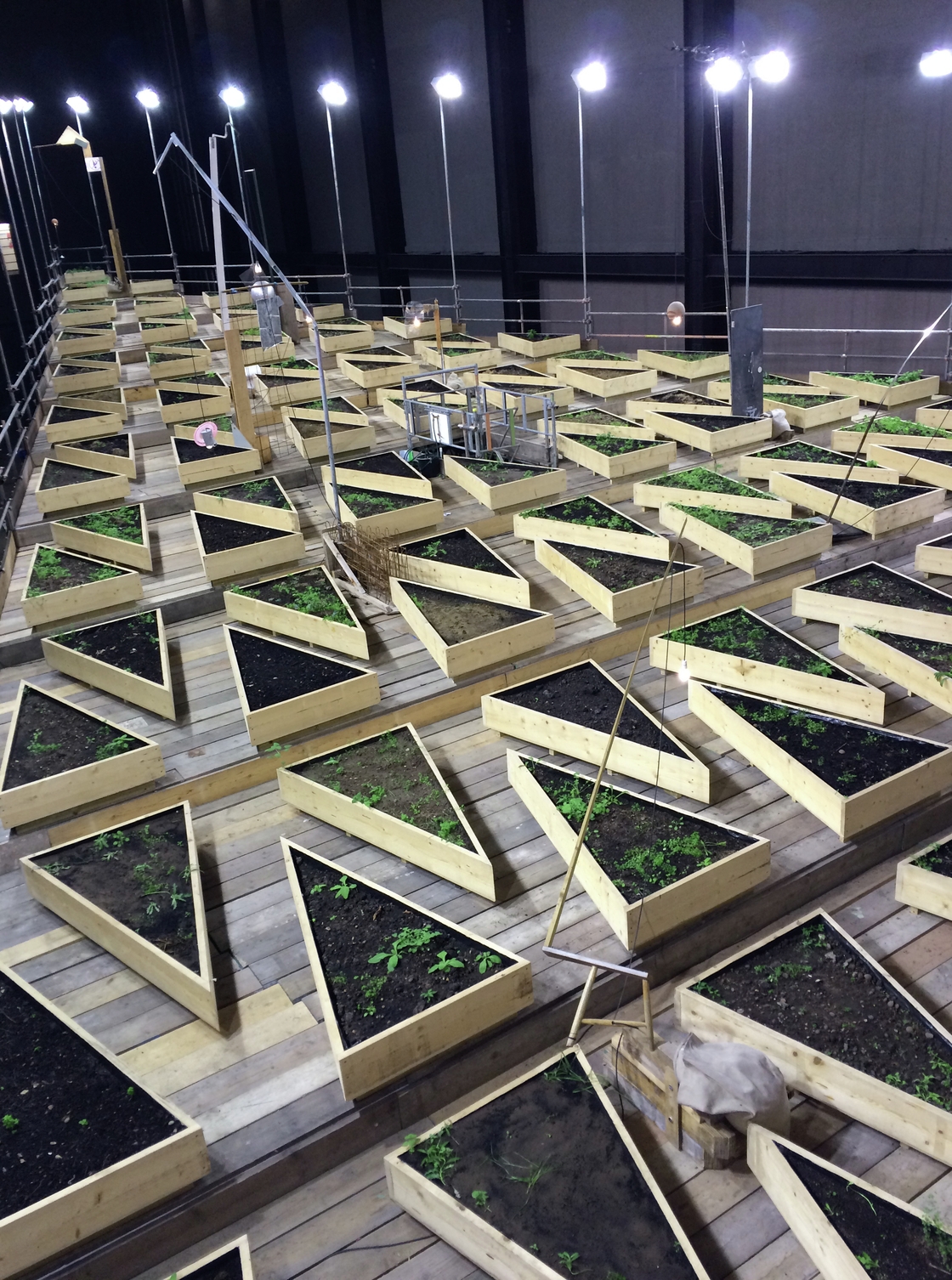

Abraham Cruzvillegas' stunning installation Empty Lot currently fills the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. He sat down with poet and author of Edgelands: Journey's into England's True Wilderness, Paul Farley, to talk about earth, art and chance.

Paul Farley I remember once standing in front of Walter De Maria’s The Earth Room in New York, it’s the first time I’d seen contained earth in a room in that sort of situation. It’s sterilised as they don’t want things growing, but there is still someone there tending to the soil. It’s a strange kind of gardeing because he is actually suppressing. He’s watching out for toadstools or mushrooms, he’s watching out for shoots that have blown in or a seed that somebody has walked in from Central Park, and he is keeping it at a steady state. I read somewhere that the track of the sun across the gallery floor dries the earth out in a path across it and he has to water it. I suppose Empty Lot is going to have that too now, while it’s here for the next few months it’s going to be looked after, but in a different way from The Earth Room because you accept that things might grow.

Abraham Cruvillegas I was trying to propose a question: Who am I? Which is a very dangerous question because it normally leads you to think about genealogy about history, geography, politics, migration, and economics and so on. So I arrived at this very simple thing, maybe I am an empty lot because of what it represents and what it means, in my own experience of course. There will be someone watering the earth, who is not a gardener, so if something grows they will not be gardening, just providing the minimum for something to grow: light and warmth. They’ll do this during opening hours, so it’s not necessarily a performance, but there is some activity. But I want to think also that this activity is not the most important one, because I’ve seen many worms and bugs, little beetles, and I’m not thinking, or not mentioning spores, and many, many things that we don’t see, but there is a lot of activity already there. We have little clay bowls as our first layer, then compost, and then the soil that came from the parks, and that’s where something can potentially come from – hidden roots for example. It’s not that I’m hoping that something will happen, I’m hoping that it’s continuous; the size of the Turbine Hall is so impressive because of the scale, but the real drama is microscopic.

PF That’s right, to really see it, or to experience it, requires a huge adjustment of scale, the micro to macro is wonderful. One of the things that’s impressed me about your work when I’ve seen it over the years, especially I remember your residency here a few years ago, is your willingness not to categorise things or materials. You quite happily will have things that are organic and inorganic working together and I love the surprise and adventure of that. Let’s move away from talking about gardening. This isn’t just soil. Soil is incredibly interesting because of how loaded it is, in any culture. The English war poet Edward Thomas went off to fight in the First World War and when asked what he was fighting for, he leaned over and picked up some earth and said ‘this is what I’m fighting for’. What made you chose soil? And what made you choose the soil you’ve chosen, because it’s come from places all over London.

AC What you said is very important to me. The real purpose of my work in general is about trying to understand the idea of people trying to own a piece of land. This is my personal story, my experience. I haven’t lived through a war, but I’ve been in constant struggle as we all do in our different ways, and if we don’t arrive at a kind of awareness then we are wasting our time, and our life. I am very grateful to my parents because they didn’t give me land, but the idea of how to be proud of the way you relate yourself to the earth; meaning fertility, meaning nature, meaning the landscape and the horizon.

PF Tell me about Mexico City in the 1960s and 70s. What’s happening there in terms of people’s land use? Were people moving towards the centre of the city or away from it?

AC After the Mexican revolution of 1910—1920 there was a strong desire and drive to construct the Mexican identity, which of course is a myth. As a country we have many languages and multiple cultures, which means difference and great diversity. We are not a homogenous society but the government wanted to consolidate the nation in to one thing — impossible. And suddenly in the 1930s there was a very important discovery for the economy — oil. Oil became the most important economic force. Many people left the countryside to go to the cities, and ended up taking land illegally, as my parents did. They chose a piece of land that was volcanic rock so nothing grows there. The nice thing about it was that people organised themselves to fight for the property of the land, to fight for education and having a school, having a market, having electricity, water, sewerage services – but in the context of not only an impoverished economy but also a very corrupt one. Despite this, people, my family included, made something very beautiful out of this – a community. It became very politicised and critical to the government, so it became a national movement, and the leaders of this movement were women, mothers, because the men had to go to out to work. We attended many demonstrations against the government and American intervention. That process led everybody to understand that you can do anything. The construction was done by everybody. Work became sharing and building together, which was an amazing process of togetherness.

PF Would the word ‘Autoconstrucción’ have been common currency in1970s Mexico?

AC Yes. It means very literally ‘self-constructed’. This is how I’ve been trying to understand the way I became myself. So when I call these works auto-construccion, it’s not just the way we made these houses, but it could be translated as self-constructing. The shapes of the houses are often very chaotic, even inefficient I would say, and very contradictory in many ways, because there is no architect involved. There is no planning, no design, no budget, and many times there are no ideas, but needs. The main material in fact is not the rocks or the stones or the wood, but the specific need. Scarcity would be the main material. And with scarcity you can make everything.

PF When I was looking at Empty Lot I was re-energised in my love for this idea of auto-construction. We’re almost the same age, but it was a very different story that happened in the UK at that time. Working-class people were moved out of cities because the housing stock was poor after the war. Cities had been heavily bombed, so we all moved out, not in. And we moved to spaces that had been constructed largely by local and central government; and the new-build housing stock, is almost all modernist — it’s not Le Corbusier — but it’s trickle-down modernist, because they’re realised that it’s cheap to build this sort of stuff quickly. Our back garden was delivered to us. The houses were so new there was no garden, just a piece of concrete and so a lorry came, full of soil, and emptied it behind the house and my father came out and said ‘right, there’s our garden’ and we got to work. The odd thing was that we knew there was nothing underneath the soil. We knew we were living in a totally artificial space.

AC For this project, we contacted every possible place in London where we could possibly get soil, including Buckingham Palace and private gardens – even people who work at Tate. People began bringing little bags of soil and so it became a kind of democracy. A collaboration with the city. In England you have so many words for these spaces; commons, greens, meadows, gardens, parks. It is a new way of looking at landscape.

PF You seem keen to stress this work isn’t simply autobiographical, and it’s not all about you. TS Eliot, who wrote The Wasteland, said the best poetry is an escape from personality, it’s not about you.

AC Exactly. It is about everybody.

PF You’re a sculptor but do you have a relationship with poetry?

AC Very much so. In the catalogue for this work, they gave me 60 pages to do with what I wished. So I piled up lots of reference images – I say pile as I’m a sculptor so the way I work normally is to pile things – as well as poetry. Since I was a teenager I have been a poetry lover and I’m very interested in the group Los Contemporaneos, who were active in Mexico in the 1920s, and of course I still read poetry from my contemporaries now, such as Gabriela Jauregui, and I love William Carlos Williams; I often quote them in my publications. Dylan Thomas is also a big inspiration for me – I could keep adding names…

PF It’s music to me ears when people cross those boundaries. Can I ask you about playfulness? When I’m writing I have to remind myself to play a bit, otherwise the words doe on the page. Is it like that for you as a sculptor?

AC Yes. The other day I went to collect some soil from a school here in London; so instead of just going to collect soil we arranged, say, a lecture, for eight and nine-year-old kids. I probably got the best questions that I’ve ever had in my life. I’m very happy that I have constructed a space in which I can become a child whilst working. This kind of playfulness you just described, like piling things in a way that they’re all about to collapse; at that moment, my work is finished. I have the privilege of being an artist – I would be stupid not to take advantage of the learning that means being able to play in such a troubled society and universe.

Hyundai Commission 2015: Abraham Cruzvillegas, Tate Modern Turbine Hall, curated by Mark Godfrey with Fiontán Moran, 13 October 2015 – 3 April 2016

更多