One day in 1999, in northeastern China, a thirty-two-year-old man who had studied photography at an art school picked up a little amateur video camera and filmed, by himself, for almost two years, the disappearance of China’s largest metallurgical complex. The result was West of the Tracks (2003), a masterly film that lasts nine hours, experienced by many of us as marking the emergence of a filmmaker and of a unique way of embodying cinema. It was the beginning of the Wang Bing phenomenon.

Since then, Wang Bing has been constantly with us. In twenty films made in the course of as many years, with humility and extraordinary determination, a monumental oeuvre has emerged. It is a body of work that encompasses, like two sides of the same coin, the anthropological films in which the filmmaker undertakes to follow the traces of those excluded from the Chinese economic miracle and the historical films in which the words of the last survivors of the “anti-rightist” campaigns of Mao Zedong are collected and preserved. Obliged to cut up this enormous body of work, we have chosen to explore only the former. In these films, a form is invented, the imprint of the obstinate presence of Wang Bing following on the heels of others, the virtuosic framing of a world in perpetual motion, the radiant humanity of this walking eye.

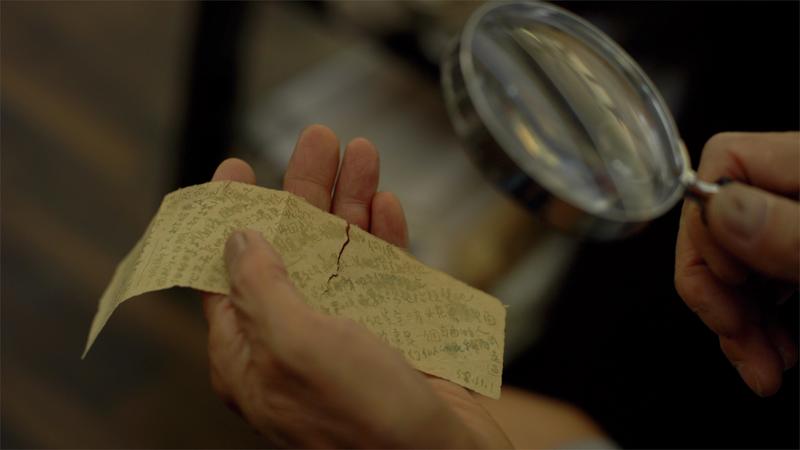

For Wang Bing, making films is born of an urgent need to question his own time, his own country, to establish without delay an alternative to official media coverage, oscillating between propaganda and censorship. Wang Bing’s films are pervaded by a question: how to display the lives of those nameless Chinese whom the “socialist market economy” has ignored, disdained, or exploited.

The political scope of Wang Bing’s films, never openly declared, is manifest therefore in an ethics of patience, of concentration, of persistence. Just being there, not too close, not too far away, waiting, not leaving, not intervening, knowing nothing beforehand, letting the truth of his subject unfold on its own: this minimal approach reflects his willingness to submit to whatever happens. But, however much he may cede the foreground to others, Wang Bing himself does not disappear. Everything is seen and heard through his camera, the sole point of capture. The sound of his breath or of his footsteps, a worker’s question (“Are you filming?”), attest to the unseen omnipresence, like a sensitive filter, of his filming body.

- Dominique Païni and Diane Dufour