The technician works in an empirical way. They have a direct approach to things and materials. They know the secrets of matter, the evidence. It turns out their tools and skills can expand techniques of cognition. The technician can alternate between processes of production, and influence the constantly changing techniques of the observer. For Jean-Luc Moulène life itself is a technique.

Técnico libertário [technicien libertaire, or libertarian technician] is much like the figure of the bricoleur, who operates with the technique of bricolage, assembling and testing different forms and materials. He doesn’t apply only one skill or one specialization, he uses various fabrication techniques, thus his work is eclectic. As Moulène says: “my activity is to free myself from categories”. Technicien libertaire is a metaphor for Moulène’s method rather than an existing and historically sanctioned term; and fortunately, one can recognize a solid avant-garde legacy behind it. An investigation of the origin of this formulation has just started and will be further elaborated in the publication accompanying the Porto exhibition, which as such, will examine Moulène’s eclectic and empirical techniques in direct interaction with Casa São Roque’s bourgeois interiors.

The term libertaire was coined by Joseph Déjacque in 1857. Libertarianism is an existing political current that affirms liberty, autonomy, political and economic freedom. In the past two centuries, it was related to different social strains of anarchism and liberalism, attempting to challenge the latter one. Technicien libertaire was first applied to Moulène’s work in 1997 by Vincent Labaume in his text The Paradise of Suspicion. Labaume recalls how he indirectly came across this expression through Pier Paolo Pasolini’s essay The Cinema of Poetry, in which similar vocabulary is employed to explicate Jean-Luc Godard’s cinematographic techniques, which are poetical. In this sense, technical freedom is poetic – and therefore close to Moulène’s gesture: the technician is a poet. This designation also returns in 2009 in Briony Fer’s text on Moulène’s œuvre directly entitled Technicien libertaire.

Let us not forget Antonin Artaud’s words: “I cannot conceive of a work that is detached from life”, as Moulène’s practice is well informed by this legacy – from the Theatre of Cruelty to the Situationists movement – in which spectacle was a model of society. In the 1970s he collaborated as an actor in performances by Actionist Hermann Nitsch, and was close to Michel Journiac, who treated the body as “social meat”. They were all using photography as evidence. This is how Jean-Luc Moulène’s work emerged from photography, from what he called “documents” that remained his main tool for many years, until – under the constant alternation and transforming protocols – they developed into three-dimensional objects and sculptures. His techniques extended to industrial manufacturing, carpentry, found materials, painting, 3D printing, handcrafts such as ceramics, glass blowing, and bronze foundry production. “I operate in material culture, sociology, anthropology” says Moulène. “Society, people exchange through objects, so these objects are always charged with something related to society, and to the people that used these objects”.

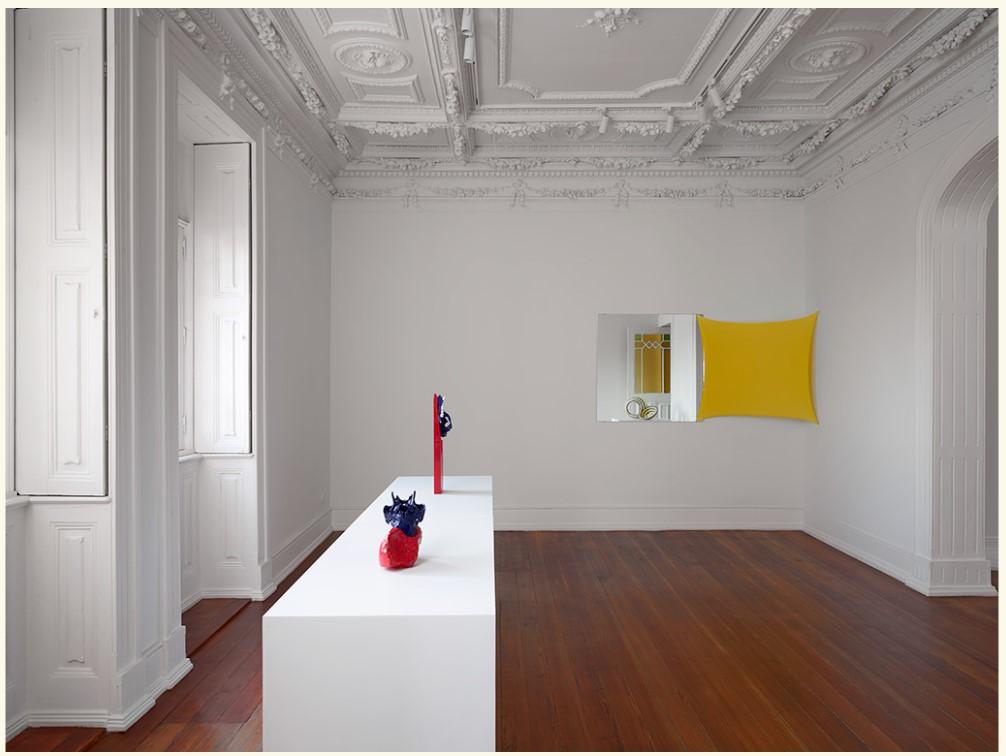

For Jean-Luc Moulène the object is an event of perception. The artist will not provide a clear user’s manual. It is the viewer who has to make a discovery. “The artwork is a place of conflict – the viewer has to find his own way and position”. In the Casa São Roque exhibition, we will unveil many riddles and new works that were made during the coronavirus pandemic in the artist’s lower Normandy studio in Le Buisson, where he moved from Paris in 2019, a few months prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. These objects are some of the first executed in the artist’s new living conditions, created in his new studio space, which was recently completed in 2021. Among others, they include yellow Compas made of one wooden branch cut in two halves, one of which contains a pencil that can draw, TransBébu – a transformed plastic doll with a new glass-blown head, and a living sculpture Densités comprised of two Sophora plants wrapped in industrial metal mesh. One will also find ça ouvre, ça ouvrepas (It opens, it does not open) assembled especially for Casa São Roque’s main floor. This large object is made of cardboard pieces glued together with colonial Portuguese and Brazilian trunks manufactured in Lisbon and Rio de Janeiro. Interestingly, as we learn from the label, one was “Awarded in 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris”, and the other, advertised in an affixed notice dated 1900: “For travels and export between Kingdom, Islands and Africa”.

更多